Your truly is not keen about having to think as much about stock market price levels as seems warranted of late. It’s pretty obvious AI plays are in a monster bubble, but that does not mean they won’t go even higher before reality drags them back to earth. As we’ve said, historically a stock market rout, unless fueled by lots of debt as in the Great Crash, does not generate a crisis but does damage the economy though investors pulling way back on spending and capital expenditures. That loss of demand is recessionary and can produce deflation and zombification. So the hangover can still do a lot of harm.

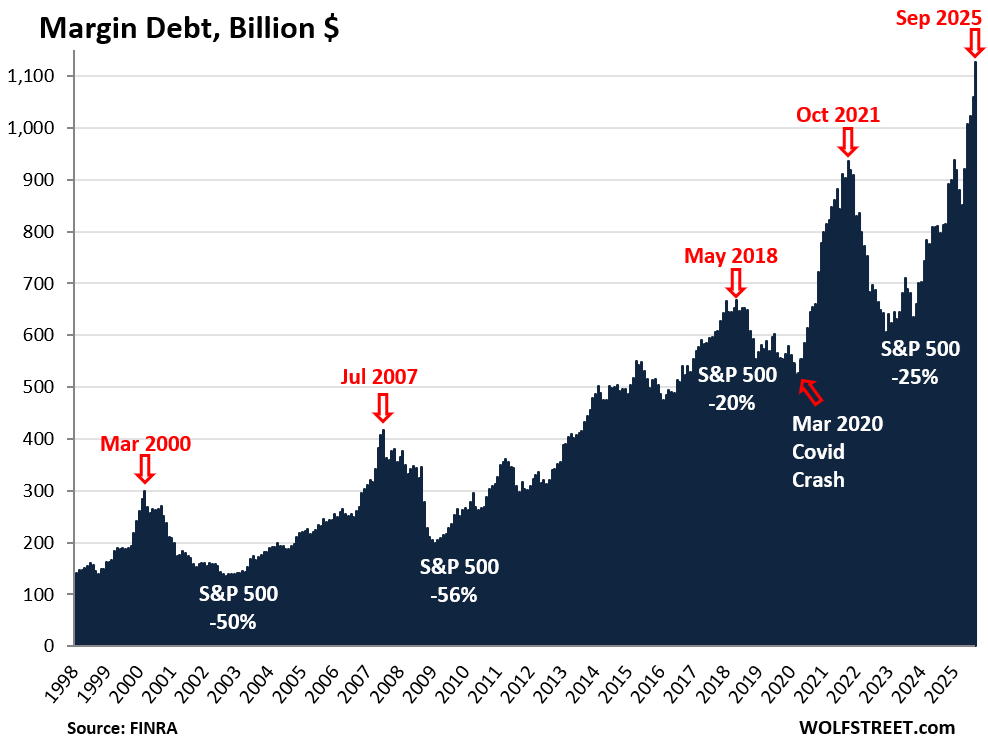

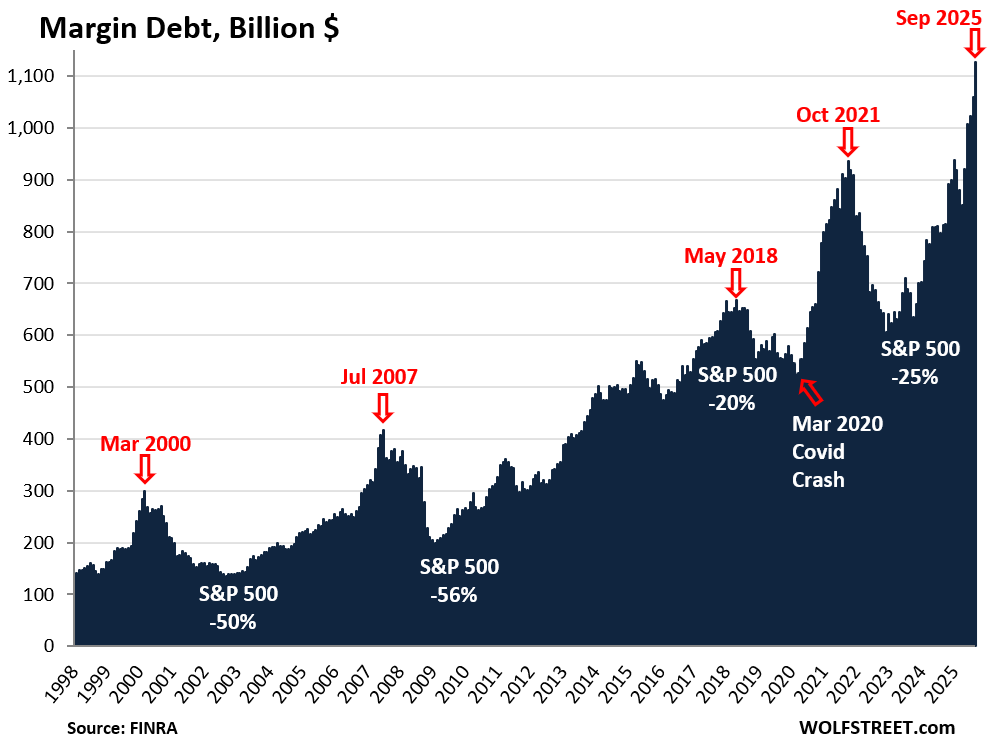

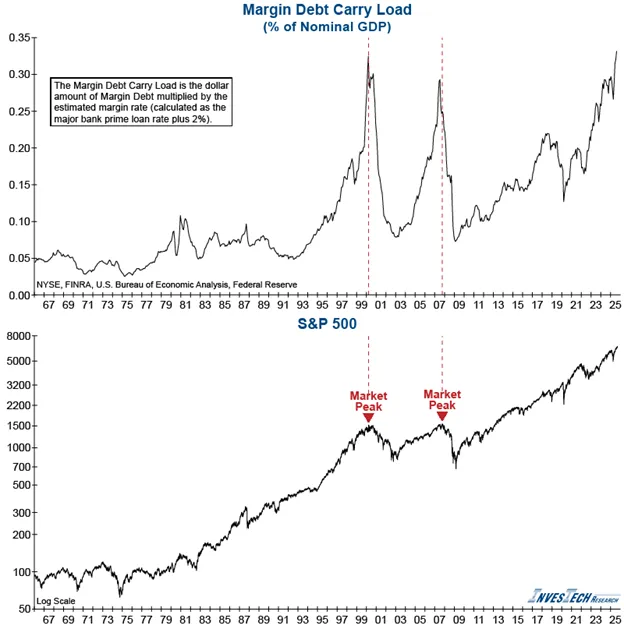

Some market-watching sites, including Wolf Richter’s, have been sounding alarms about US margin debt hitting an all-time high. Here’s Wolf’s chart and a snippet from his commentary:

Leverage in the stock market has been spiking since April. In September, margin debt – the amount investors borrowed from their brokers – spiked by another 6.3%, or by $67 billion, from August to a record $1.13 trillion…

The additional leverage – borrowed money flowing into the stock market – creates buying pressure and drives stock prices higher. Leverage is the great accelerator on the way up, but it’s also the great accelerator on the way down. Multi-month surges in margin debt, jumping from new high to new high, indicate excessive speculation and risk-taking and have invariably led to sharp selloffs:

The wee problem is that while the picture above is accurate, it doesn’t add as much to what we know about stock market frothiness as one might think. Borrowing against stocks is strictly regulated. So when market prices go up a lot, so to does margin borrowing. The chart above does give another demonstration of how sharply stock prices have risen and that when those spells of wild enthusiasm wear off, the forced deleveraging accelerates the plunge.

A rejoinder from the admittedly mainstream Morningstar in August:

Margin debt isn’t a red flag for one investor.

One of the explanations put forward recently for the record-breaking rally in the U.S. stock market was the equally record-breaking amount of margin debt that had been incurred in the process. Money borrowed to invest in shares topped $1 trillion in August.

For Brian Jacobs of Aptus Capital, however, this is not the five-alarm fire it sounds and is less ominous than investors might suspect. Economist David Rosenberg posted on X a few weeks back that the number was “pretty scary” but Jacobs contends it’s merely a coincident indicator, a symptom of the market’s meteoric rise, rather than a signal of its imminent demise.

Jacobs writes in a recent investment blog: “It (margin debt) moves with the market. When equities rise, account values increase, and investors naturally take on more leverage. Margin debt rising 25% over the last year? The S&P 500 SPX is up about the same. Margin debt has almost doubled over the last five years? The S&P 500 is up about the same.”

But having said that, while a crude look at margin debt levels may not do more than demonstrate that stocks have gone up a lot, and quickly of late, other ways of parsing margin borrowing do paint a worrisome picture. At the end of September, Cory McPherson at Pro-Active Capital published Margin Debt Showing Investors Going All In. Key sections:

From the August [2025] numbers, margin debt relative to nominal GDP sits at 3.48%. The record high reading was 3.97% in October 2021. For historical context though, the peak in that ratio was 2.6% in the dot-com bubble days in 2000, and 2.5% in 2007 before the great recession.

Another way to look at is Margin Debt Carry Load. This factors in the interest being paid on the margin debt. The chart below shows the dollar amount of margin debt multiplied by the estimated margin rate, which is calculated as the major bank prime rate plus 2%. This is then put in % of nominal GDP. You can see we have now reached levels seen during the last stages of the dot-com bubble days in 2000. Margin debt, though, is definitely not a timing indicator. This can continue to get higher and higher, just as the stock market can. What it can do, though, is create violent downturns in the market. When an investor owns stock on margin and that stock goes down a certain amount, the brokerage forces the investor to sell, which can create an elevator down affect, similar to what we saw in April of this year.

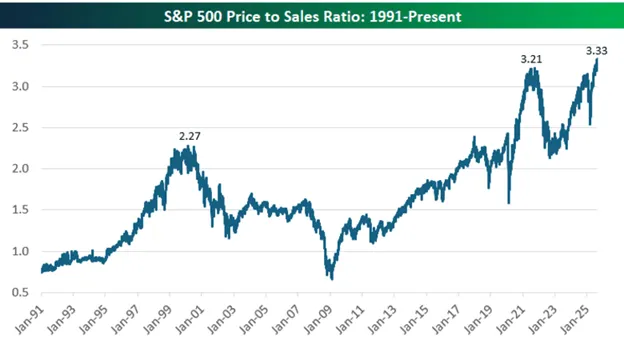

A fundamental metric on the stock market has also reached extreme heights recently. The price to sales ratio is a valuation metric that compares a company’s stock price to its revenue. Basically, a measure of what investors are willing to pay for each dollar of sales from a company. In looking at the price to sales ratio of the S&P 500 (taking the market cap of the S&P 500 and dividing by the total sales of all companies in the S&P 500 over the past 12 months), you can see we’ve surpassed last year’s and 2021’s peak in the ratio. It is also way past the peak that was seen in the dot-com bubble days, which is thought to be one of if not the biggest stock market bubbles in history. Much of this is being driven of course by technology stocks and the AI boom we’ve seen over the last few years. Stock prices have got way ahead of actual sales. While overvaluation doesn’t cause market drops or bear markets, they do often precede them.

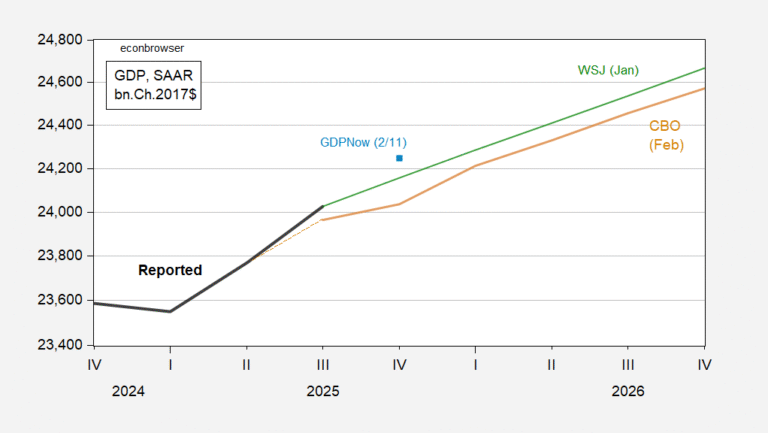

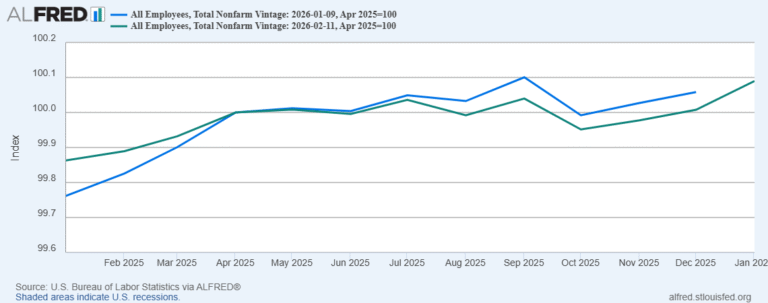

McPherson then considers some real economy data anomalies, that the big downward jobs revision happened without a recession, and that the Conference Boards leading indicators have been falling for three years while its coincident indicator continues to rise. It seems that running very large fiscal deficits for a while can produce confusing results.