Yves here. In a bit of synchronicity, I saw this Richard Murphy post almost at the same time as Colonel Smithers recommended it via e-mail. Keep in mind that orthodox economists, as Steve Keen in particular has lamented long-form, basically ignore banking and finance, That means they can also turn a blind eye to the damage it does and rely instead on ideology, like financial deepening (as in more finance activities relative to the size of the economy) being better. As we pointed out, none other than the IMF concluded the reverse in 2015:

But the recent IMF paper, Rethinking Financial Deepening: Stability and Growth in Emerging Markets, is particularly deadly. Even though it focused on the impact of financial development on growth in emerging markets, its authors clearly viewed the findings as germane to advanced economies. Their conclusion was that the growth benefits of financial deepening were positive only up to a certain point, and after that point, increased depth became a drag. But what is most surprising about the IMF paper is that the growth benefit of more complex and extensive banking systems topped out at a comparatively low level of size and sophistication.

The paper concluded that Poland (recall as of the early 2010s) was at the optimal level. More finance (unless perhaps well regulated, a condition not observed in the wild) reduces growth.

Even though Murphy’s case study is the UK, the harms he lists apply fully to the US.

By Richard Murphy, Emeritus Professor of Accounting Practice at Sheffield University Management School and a director of Tax Research LLP. Originally published at Funding the Future

Why does Britain feel poorer, more unequal and less productive than it should be?

In this Funding the Future podcast, I speak with John Christensen, co-founder of the Tax Justice Network, about the finance curse, which occurs when banking and financial services grow beyond any socially useful scale.

Drawing on John’s work in Jersey and decades of UK experience, we explain how finance crowds out real economic activity, drives up housing costs, drains talent, captures politics and ultimately undermines democracy. We also discuss new research showing the staggering cost of this failure to every household in Britain, and what can be done to reverse it.

This is the audio version:

There is no transcript of this as it would be far too long, but this is a summary instead:

The Finance Curse: How Britain Was Hollowed Out

I recently recorded another Funding the Future podcast with my long-standing friend and collaborator John Christensen, with whom I co-founded the Tax Justice Network almost a quarter of a century ago. This conversation followed on from an earlier discussion about what has become known as the finance curse. This is an idea John has spent much of his working life developing, and one which I believe is central to understanding why the UK economy is in such deep difficulty today.

The finance curse describes what happens when a financial services sector grows beyond any socially useful scale and begins actively to damage the economy and the political system that hosts it. John’s insights into this emerged originally from his work as economic adviser to the government of Jersey, where he was formally tasked with maintaining a balanced and diversified economy, and where he instead watched, in real time, as finance crowded out almost everything else.

From the “Jersey disease” to the Finance Curse

John explained how the idea first emerged from observing Jersey’s transformation in the 1980s and 1990s. What had once been an economy based on agriculture, horticulture, tourism and small-scale enterprise was rapidly overwhelmed by banks, law firms and accounting firms serving offshore finance. This process was so destructive that John and an academic colleague initially labelled it the “Jersey disease”.

Over time, however, it became clear that what was happening in Jersey closely mirrored the better-known resource curse, where countries rich in oil or minerals experience economic distortion, political corruption and weakened democracy. In the financial case, it is not oil or gas but banking and financial services that behave like a cuckoo in the nest, by squeezing out other sectors and capturing political power.

John stressed that the harms of the finance curse are not static. They evolve over time, affecting currency values, labour markets, democracy, inequality and investment. Crucially, they impose real and measurable costs on households — costs which we now know amount to tens of thousands of pounds per person in the UK.

>Seeing the Damage With Our Own Eyes

I reflected on how stark this transformation has been in physical as well as economic terms. The Channel Islands I visited as a child, places shaped by farming, fishing and tourism, are unrecognisable today. The harbour areas and town centres now resemble anonymous financial districts that could be anywhere in the world.

The same is true of London. The City I entered in 1979, when manufacturing and productive enterprise still dominated the corporate landscape, has been replaced by an economy centred on finance, rent extraction and speculation. This matters because the UK, unlike larger economies such as the US, has allowed finance to become overwhelmingly dominant, hollowing out its industrial base in the process.

Six Ways Finance Destroys Economies

John then set out six core mechanisms through which the finance curse operates. These mechanisms not only apply to Jersey, but to the UK as a whole.

First, there is a form of Dutch disease. Finance drives up asset prices, wages and land values, making other sectors uncompetitive. In Jersey, this was visible in house prices rising at twice the UK rate for a decade, making it impossible for workers outside finance to live there. In Britain, the same process has priced entire generations out of housing, particularly in London and the South East.

Second, the labour market is distorted. Highly educated and talented people are drawn into finance by inflated pay, draining skills from engineering, manufacturing and research. This brain drain undermines innovation and long-term productivity, leaving the real economy weaker as finance grows stronger.

Third, financialisation accelerates wealth extraction. Private equity and hedge funds acquire viable businesses, load them with debt, strip assets, suppress wages and extract rents. John and I both noted how this process destroys productive capacity while generating paper profits often routed offshore.

Fourth, finance concentrates geographically. Wealth, talent and political attention are sucked into financial hubs, and above all, London, while the rest of the country is starved of investment. This deepens regional inequality and fuels misleading narratives that places like Scotland and Wales do not create value, when in reality their value is extracted and booked elsewhere.

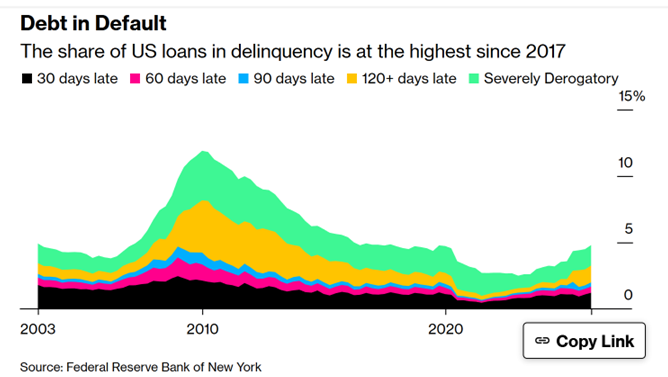

Fifth, everyday life becomes more expensive. Rents rise, small businesses are priced out, high streets hollow out and social mobility collapses. The free-for-all in mortgage lending since the 1970s has left millions burdened with unsustainable debt, reversing decades of post-war progress.

Sixth, and most dangerously, finance captures politics. Because financial capital is highly mobile, it can threaten to relocate unless it gets tax cuts, deregulation and political deference. This gives banks and financial institutions enormous leverage over governments, political parties and the media — undermining democracy itself.

The Staggering Cost of the Finance Curse

We then turned to the evidence on cost. Research commissioned by the Tax Justice Network, from the University of Sheffield and the University of Massachusetts, estimated that between 1995 and 2015, the finance curse cost each person in the UK around £67,500, or more than £3,000 per year. In total, the losses amount to around £4.5 trillion.

These costs arise from:

- misallocated investment,

- excessive mergers and acquisitions,

- underinvestment in innovation,

- labour misallocation,

- bank bailouts and

- vast bonus payments.

The idea that private banks allocate capital efficiently, John argued, is simply false. The evidence shows the opposite.

What Can Be Done?

The obvious conclusion is that the City of London is not the “jewel in the crown” it is so often claimed to be. It has been a drag on the UK economy for decades. Reining it in will require stronger regulation, public control over capital allocation, regional and national investment banks, and serious competition policy.

John also argued for confronting the ideological roots of the problem, which he explores in his forthcoming film The Finance Curse. These include the shareholder revolution, the dismantling of antitrust law, and the race-to-the-bottom ideology of national “competitiveness” promoted by global elites.

The task ahead is not simple, but continuing to allow finance to dominate unchecked would lead to economic stagnation, social division, and democratic decay. If we want an economy that works for people rather than against them, confronting the finance curse is unavoidable.