One of the weird disconnects about the time in which we are living is more and more acknowledgment of survival systems under serious stress, namely climate-change heat waves, fires, intense rainfall, and in other areas, water shortages wreaking havoc with agricultural production. And that’s before getting to self-inflicted high energy prices in Europe adding another level of social and political pressure.

It may seem alarmist to talk about future Arab Spring level revolts. And yours truly is not saying they are imminent. But the flip side is the direction of travel seems obvious. Enough immiseration of ordinary citizens eventually produces blowback, whether food riots (see the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 2007-2008 food price spikes), regime-change attempts of the Arab Spring sort, or fuel price protests a la Gillets Jaunes.

As William Gibson said, “The future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed,” applies to our slow-motion polycrisis.

And because whether it is sensible to buy a burrito with a buy now, pay later loan seems more pressing than accelerating resource pressures, it seems just too distressing to consider that food riots or other forms of “I need mine” violence may be coming sooner than most would like to think. The headline for a summary of a 2025 study confirms the sense that the climate-change-induced deterioration of food systems is oddly being ignored. From Heat and drought are quietly hurting crop yields:

More frequent hot weather and droughts have dealt a significant blow to crop yields, especially for key grains like wheat, barley, and maize, according to a Stanford study published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The analysis finds that warming and air dryness – a key factor in crop stress – have surged in nearly every major agricultural region, with some areas experiencing growing seasons hotter than nearly any season 50 years ago….

The study estimates that global yields of barley, maize, and wheat are 4 to 13 percent lower than they would have been without climate trends. In most cases, the losses have outweighed the benefits of increased carbon dioxide, which can improve plant growth and yield by boosting photosynthesis, among other mechanisms…

The findings echo concerns raised in a study published in March that found U.S. agricultural productivity could slow dramatically in coming decades without major investment in climate adaptation…

[Study lead author David] Lobell adds that the surprise many people express may simply be because they had been hoping the climate science was wrong, or because they underestimated the impact a 5% or 10% yield loss would have. “I think when people hear 5% they tend to think it’s a small number. But then you live through it and see it’s enough to shift markets. We’re talking about enough food for hundreds of millions of people.”

Keep in mind that wheat alone provides 20% of humanity’s food calories and protein. New Scientist chimed in with Is the climate change food crisis even worse than we imagined? in late 2024:

You have probably already noticed that the price of many of the foods in your grocery basket has risen…

What is driving prices up is complex, but one of the biggest factors is climate change. In the short term, extreme weather caused by a warming climate has had devastating consequences for growers. In northern Europe, for instance, torrential rains in spring 2024 left fields too sodden to harvest vegetables or plant new crops. Meanwhile, a drought in Morocco, which typically exports a lot of vegetables to Europe, meant there wasn’t enough water for irrigation. The result was soaring prices for potatoes and carrots…

Not only are newer climate models projecting much stronger effects, both positive and negative, but the latest crop models also suggest the impact on yields will be much greater too, says Jonas Jägermeyr, a climate scientist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York….

But current models also have some serious limitations. “Realistic projections probably would be a little bit less optimistic,” says Jägermeyr, noting that climate models aren’t good at projecting extreme events and that crop models tend to underestimate impact.

Another major limitation is that these models don’t consider the risk of pests and diseases. As the planet warms and becomes more humid, some pathogens will spread to areas where they haven’t been able to survive before…

So far, it is also proving harder for farmers to nevertheless increasing…via technology but also measures that amount to eating our seed corn on a planetary scale:

The other reason for rising food production is that the global area used for growing crops is expanding rapidly. This often involves turning forests into farmland, which is catastrophic for biodiversity. Clearing trees also puts a lot more CO2 into the atmosphere, adding to farming’s already large carbon footprint – about a third of our greenhouse emissions come from agriculture.

Alarmingly, we seem to be at the start of a vicious cycle: global warming is making it harder to grow food, so farming is becoming more emissions-intensive to keep up, leading to yet more warming. The rising temperature will also amplify other threats to world food production, including ocean acidification, groundwater depletion and soil loss, intensifying that cycle further – for instance, hotter temperatures mean farmers need to use more groundwater for irrigation.

To add to this cheery picture, droughts are part of the agricultural shortfall problem as well as being generally hazardous to living things, such as people. From the Guardian in July:

Drought is pushing tens of millions of people to the edge of starvation around the world, in a foretaste of a global crisis that is rapidly deepening with climate breakdown.

More than 90 million people in eastern and southern Africa are facing extreme hunger after record-breaking drought across many areas, ensuing widespread crop failures and the death of livestock. In Somalia, a quarter of the population is now edging towards starvation, and at least a million people have been displaced.

The situation has been years in the making. One-sixth of the population of southern Africa needed food aid last August. In Zimbabwe, last year’s corn crop was down 70% year on year, and 9,000 cattle died..

In Latin America, drought led to a severe drop in water levels in the Panama canal, grounding shipping and drastically reducing trade, and increasing costs. Traffic dropped by more than a third between October 2023 and January 2024.

By early 2024, Morocco had experienced six consecutive years of drought, leading to a 57% water deficit. In Spain, a 50% fall in olive production, driven by a lack of rainfall, has caused olive oil prices to double, while in Turkey land degradation has left 88% of the country at risk of desertification, and demands from agriculture have emptied aquifers. Dangerous sinkholes have opened up as a result of overextraction.

[Founding director of the US National Drought Mitigation Center Mark] Svoboda said: “The Mediterranean countries represent canaries in the coalmine for all modern economies. The struggles experienced by Spain, Morocco and Turkey to secure water, food and energy under persistent drought offer a preview of water futures under unchecked global warming…”

The impacts of drought stretch far beyond the borders of stricken countries. The report warned that drought had disrupted the production and supply chains of key crops such as rice, coffee and sugar. In 2023-2024, dry conditions in Thailand and India led to shortages that increased the price of sugar by 9% in the US.

Notice that these studies on droughts focus on the effects on agriculture. They don’t consider what happens when cities and regions face a crisis, as Cape Town has and Iran may be suffering. Nor do they consider what happens when citizens have to add water to the list of things. Even in the US, a few locations with very high water or sewer charges, like Birmingham, Alabama, water affordability is already an issue. And attesting to the fact that water costs can push a financially strapped household to the brink, the US has water assistance programs for low-income households. Recall we pointed out at the inception of this site that potable water was the resources set to come first under serious stress, so expect this problem to intensify in coming years.

Healing Waters gives an overview:

Affordability in the water sector is often defined as households spending no more than 3-5% of their income on water and sanitation services. However, this metric overlooks hidden costs, including:

- Purchasing firewood or gas to boil water

- Buying purification products like chlorine tablets

- Spending valuable time collecting water

These additional expenses can drive total water costs far beyond the standard affordability threshold, forcing families into impossible choices…

The Economic Burden of Water Costs

In many regions, families spend over 10% of their income on water, with extreme cases reaching 30-50%. In contrast, the average American household spends just 2% of its budget on water, which covers all household uses, not just drinking water.

Farmers are already under stress. From the Guardian in July:

More than 80% of UK farmers are worried that the “devastating” effect of the climate crisis could damage their ability to make a living, a study has found.

Farmers have warned that global heating risks Britain’s supplies of home-grown food amid wild swings in weather conditions, in new research carried out by the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU).

The study found that 87% of farmers have experienced reduced productivity in the face of recent extreme weather, 84% had suffered a fall in crop yields, and more than three-quarters had taken a hit to their income…

In stark contrast, just 2% of farmers had not experienced extreme weather in some form.

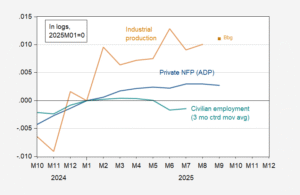

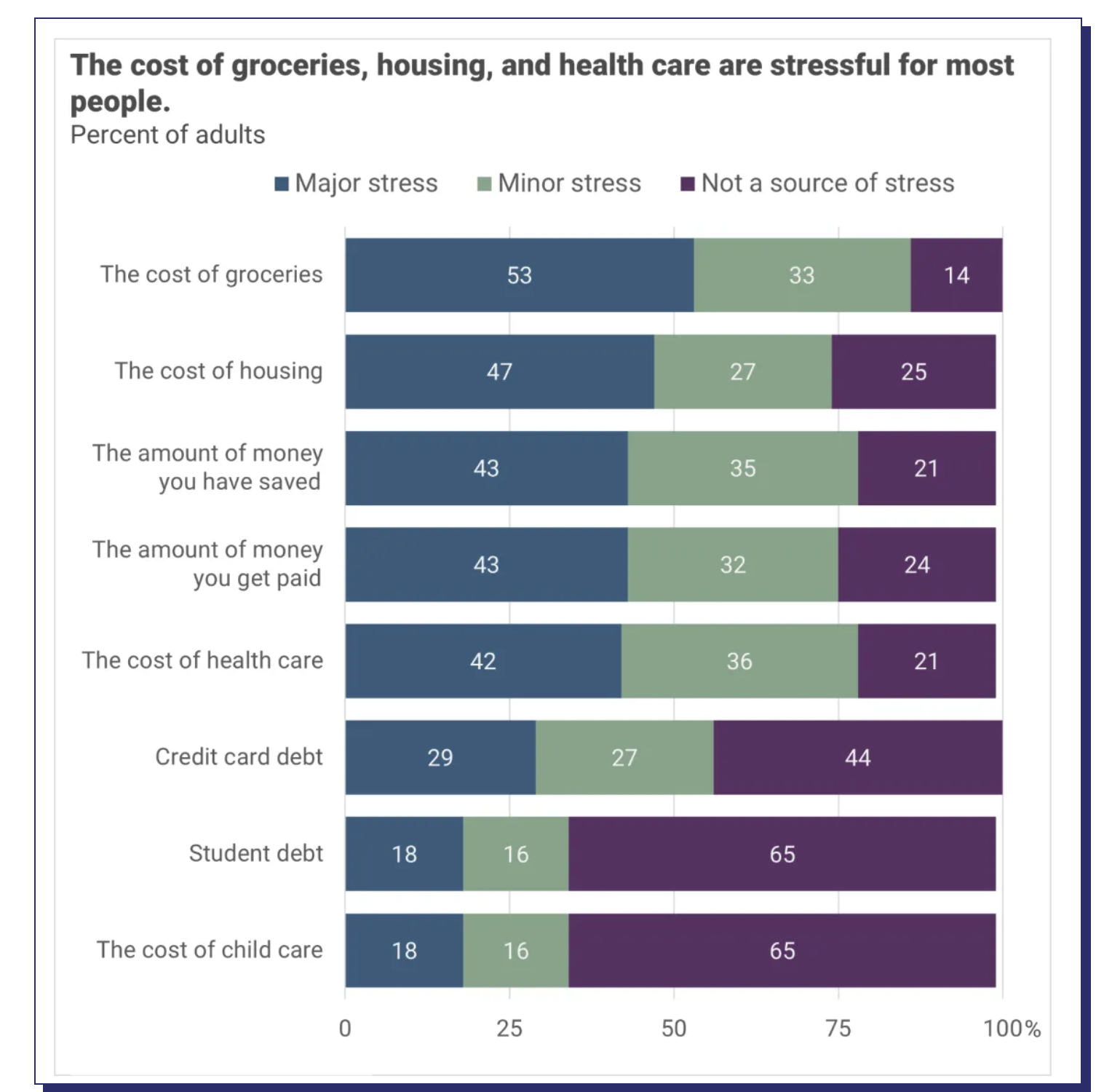

And on the consumer end, even in the theoretically not-food-shortage afflicted US, the majority of households feel food cost pressures. A key chart from a July AP/NORC survey of over 1.400 adults:

Hopefully readers in other parts of the world can chime in with data or anecdata about food worries in their part of the world.

Most readers know that the EU is now suffering form high energy prices thanks from its divorce from all things Russian, particularly its cheap gas:

It was not possible to get the legend into the screenshot, but as you might guess, darker = worse.

Gas prices around the world at August 18 show Russia at 78.3 cents a liter, the US at 92.4, and the highest price countries below:

Needless to say, there are so many governments and social system in the headlight of the freight train of more resource scarcity that it’s impossible to forecast or guess all that well about how things start to break down and how citizens act. But in advanced economies, the level of dislocation will look more and more like a failure of those in charge, both institutions and individuals, to deliver on social contracts.

In atomized America, the result is more likely to continue to be random violence and quiet desperation than revolt.

Americans are breaking down, a grown woman crying because she can’t afford to live anymore

“I’m wondering if anybody else is feeling like they’re drowning and they can’t get out. I work overtime, and I cannot get above water. I mean, I literally have no gas for next week. It was… pic.twitter.com/tS5Io7bY91

— Wall Street Apes (@WallStreetApes) August 15, 2025

But manh other countries have cities like Paris and London which are both centers of government and commerce, which makes for an easier target for collective action.

Again, this situation is far too fraught to make any firm calls, but it bears monitoring.