Here in the West, the ash (Fraxinus spp.) has long been a first-choice tree due to its dependable constitution. Today, ash comprise between 20 and 25% of the urban canopy by square foot in Fort Collins, where I live and garden. The arrival of the emerald ash borer (EAB) is certain to change that. An invasive pest, the beetle’s young feed on the living layers beneath the bark of ash trees, girdling the trees and cutting off the flow of water and nutrients between their roots and canopies. Perhaps the most concerning aspect of the spread of this pest is the mortality rate for trees it infests; nearly 100% of the ash typically used in the West are dead within several years of infestation. In large part that’s because the ash we use widely, including green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica, Zones 3–9) and white ash (F. americana, Zones 3–9) have no natural defenses against the pest, which evolved feeding on species of Asian ash that do bear natural resistance.

How EAB is spreading west

EAB has been gradually working its way across the country for the last 20 or so years since it arrived in the Upper Midwest in the early 2000s, likely as a hitchhiker in shipped wood or pallets. The weak-flying adults are a primary means of its spread there, where a patchwork of woods rich in ash trees provides the ideal conditions for this pest to cover a lot of ground. In the West, the nearly treeless Great Plains stopped its spread for years. As far as the beetle is concerned, the West itself is more or less an archipelago of treed towns separated by unnavigable food deserts. The pest is more likely to arrive in ash wood products and firewood bundles moved from one town to another. Sadly, for us, this means that though EAB won’t spread far on its own in the West, its presence in your city is only one firewood bundle away.

So far in the West, the EAB has established itself up and down the Colorado Front Range Urban corridor, the Grand Junction, (Colorado) area, and in the Portland, Oregon, area. For a detailed map of its spread by APHIS/the USDA, see here: EAB Infestation Map. The brilliant metallic-green adult beetles typically only fly a half mile or less from their host tree, meaning that if left to its own devices, the pest takes years to make its way across a city after establishment.

EAB was first detected in my region in Boulder, Colorado, in 2013 and took around seven years to cover the 60 miles to Fort Collins, likely in firewood driven between the two cities. It then took five years to cover the final three and a half miles to my street, more likely by natural flight. Finally, last summer, my shady and relatively pleasant three-block walk to the grocery store was turned into an overheated slog through what suddenly felt like a concrete jungle after around half a dozen mature ash were cut down along the route due to EAB infestations. The trees had looked just fine the summer prior, though it’s likely the pest had been in the trees for more than a year.

Symptoms of an EAB invasion

Obvious symptoms on the trees were similar to but more extreme than symptoms caused by other borers:

- Branch or twig dieback

- Reduced vigor

- Leafing out late in spring (some with tiny leaves)

- Patchy to widespread dieback in tree canopies

- Exit holes in the bark (especially up and down the trunk) where the beetles emerge after maturing

There are two signs to look out for that distinguish the EAB from other ash borers in the region, like the native and not especially harmful lilac/ash borer:

- Exit holes will have a distinctive “D” shape (⅛-inch diameter, flat on one side, and otherwise rounded)

- Widespread twig death that occurs over the entire canopy simultaneously; it can be gradual or sudden

Lilac/ash borer is already widespread across our region. It routinely causes minor or moderate twig and branch dieback on mature ash and leaves round O-shaped exit holes. It rarely causes the severe, widespread canopy damage seen with EAB and is more harmful to stressed trees. EAB successfully invades and kills virtually all American ash, even healthy, mature specimens.

Extreme weather events, like cold snaps or drought, can also cause canopy death in ash, but typically in such cases the damage is self-limiting rather than worsening with time. There also isn’t the profusion of growth from the interior of the tree crown that is associated with borers. If you see trees in your area that show damage consistent with EAB’s feeding, check in with your local county extension office. If it is in your yard, consult with a professional arborist for a diagnosis.

EAB Management

Treatment

So far, the only effective treatment for EAB is systemic insecticides. In the cases of mature specimen ash, sentimental trees, or those that provide significant benefit for your home (like a shade tree on the west side of your house), their use is often warranted. That being said, treatments aren’t cheap if done professionally, do carry some harm to nontarget insects, and must be carried out on a rolling, three-year basis to remain effective. While some smaller ash can be treated by the homeowner, I personally wouldn’t do so. The insecticide is typically applied as a soil drench, carrying greater risks to both the applicator and environment. Also, it is less effective than professional trunk injections so must be done more frequently.

Removal

In the case of young trees, those with less value to your property, or those that could be done without, removal is typically a more sustainable option—both environmentally and fiscally. Removing trees killed by this pest is often more expensive than removing healthy ones, due to dead and dying wood becoming brittle and the need to properly chip or dispose of infested wood—therefore, early removal can save money.

Replacement

If treating sounds unappealing but removal would be detrimental to your property, consider shadow planting a replacement tree. The concept is to use your mature tree as a shelter for an establishing sapling; once the mature tree starts to fail and is removed, the sapling will be fully established and grow in more quickly than one planted in full sun after the ash is removed. To do this, find a suitable replacement tree and plant the sapling far enough from your ash tree’s trunk so that removal will remain safe and as easy as possible when the time comes. A 15-foot distance between the two is a good minimum.

If removal and replacement or shadow planting is on the table, below is a quick list of shade trees adapted to our region that can make good ash replacements; all are durable and adaptable, each with its own strengths and weaknesses:

- Northern catalpa (Catalpa speciosa, Zones 4–8) is an easygoing and unique-looking shade tree with massive leaves, handsome clusters of throated white flowers in early summer, and unusual, foot-long, bean-pod-like seedpods.

- Netleaf hackberry (Celtis reticulata, Zones 4–9) is a superb wildlife tree, very adaptable, and quite drought tolerant. It is a “no frills” option that is among the toughest and best for wildlife on this list.

- Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba, Zones 3–8) has a unique leaf and form, good fall color, and a shape that is usually narrower than other options on this list.

- Honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos, Zones 3–8) is adaptable and drought tolerant, and has good fall color. There are some problems with canker in locales where these trees are stressed by extreme heat or drought on the Colorado Front Range in recent years.

- Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus, Zones 3–8) is adaptable and drought tolerant, but some forms drop large seedpods. Look for seedless (male) types, like Espresso™.

- Plains cottonwood (Populus deltoides, Zones 3–9) is an adaptable and drought-tolerant wildlife tree, though only suitable for large lots and away from buildings due to brittle, rot-prone wood. However, resulting holes and snarls make great homes for birds and critters.

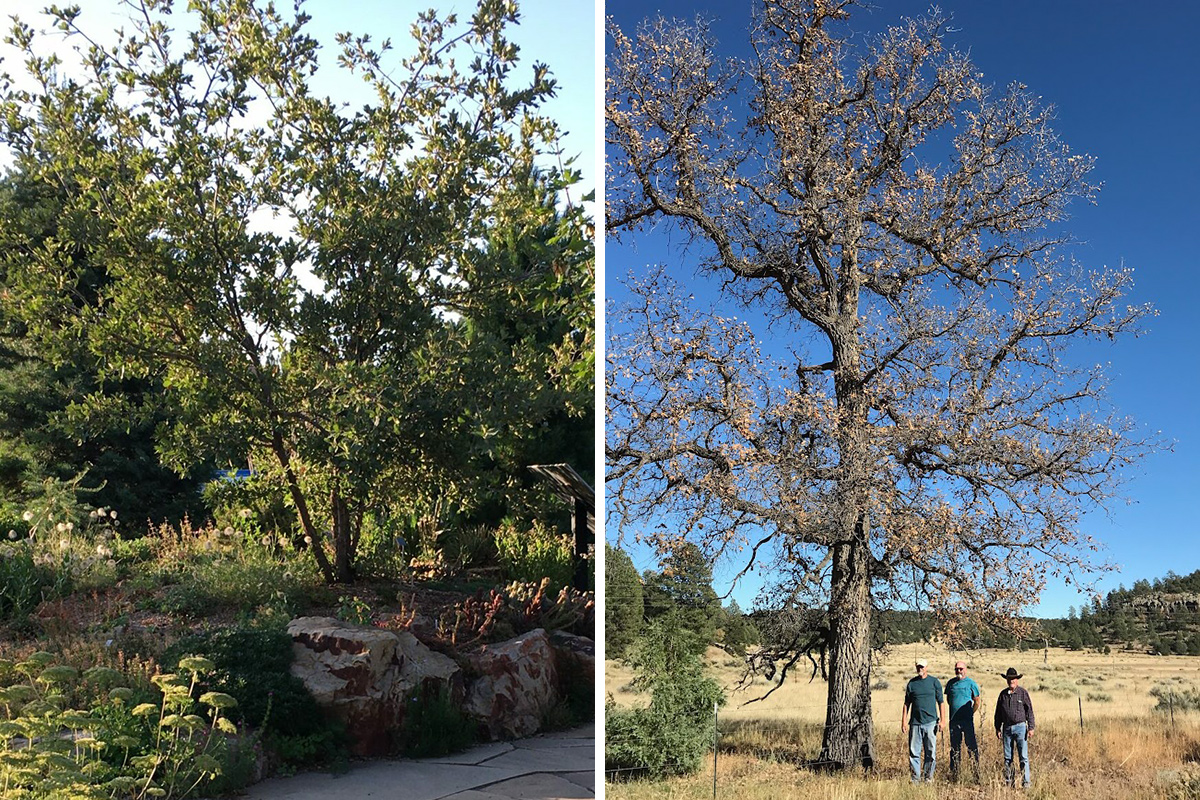

- Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii, Zones 4–8) is adaptable, drought tolerant, and has a huge variety of growth habits ranging from running shrubs to single-trunk trees. Look for those known to retain tree form, like Gila Monster™.

- Bur oak (Q. macrocarpa, Zones 3–8) is a particularly large tree that is adaptable and drought tolerant once established.

- Chinkapin oak (Q. muehlenbergii, Zones 5–7) is adaptable and drought tolerant, with some forms featuring deep, rusty red fall color.

- Shumard’s oak (Q. shumardii, Zones 5–9) is adaptable and handsome but not quite as drought tolerant as other oaks mentioned.

- Japanese pagoda/scholar tree (Styphnolobium japonicum, Zones 4–8) is an unusual summer-flowering tree (hanging clusters of cream blooms) with elegant, compound leaves that give an airy feel but can be messy due to dropped pods in summer.

- Bald cypress (Taxodium distichum, Zones 4–9) is a deciduous conifer that is more drought tolerant and adaptable than its origins in swamps may suggest but still loves soils of moderate or greater moisture. It has proven itself attractive and dependable in irrigated landscapes around Fort Collins and some other parts of the Colorado Front Range. Consider it worth trying but not entirely proven in other areas in the West.

- David elm (Ulmus davidiana, Zones 5–8) is a particularly tough elm resistant to both Dutch elm disease and elm scale (the cause of the sticky coating and black, sooty mold on everything below some elms). This tree is quite adaptable and reliable with irrigation and attains a great size.

Final thoughts

While emerald ash borer is already proving catastrophic for some places in the West, it may not reach others for years. So, having an ash in your yard now doesn’t necessarily require action if the pest hasn’t arrived in your area. If you’re in a situation like mine, with active infestations in your area and an ash-heavy tree canopy, action is warranted sooner than later. Currently, I counsel friends and family in my area to remove or shadow plant under most ash in advance of infestation, saving and professionally treating those of unique value (shade for home, sentimental, or otherwise), and replacing those removed with a lesser-used but reliable shade tree. At least an opportunity to grow a new-to-you tree is a small silver lining. With time, it’s likely that the West will replant its urban canopies to avoid more damage by these beetles. It is also possible the ash will return to our canopies, thanks to genetic work by plant breeders and scientists alike, similar to the increasingly likely return of the American chestnut (Castanea dentata, Zones 4–8) through comparable means after the chestnut blight epidemic.

Learn more about managing tree pests and diseases:

Discuss this article or ask gardening questions with a regional gardening expert on the Gardening Answers forum.

And for more Mountain West regional reports, click here.

Bryan Fischer lives and gardens at the intersection of the Great Plains and the Rockies. He is a horticulturist and the curator of plant collections for a local botanic garden.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Medium Nut Wizard 14″ for English Walnuts, Chestnuts, Golf Balls

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

For nuts 3/4″ to 4″. For English Walnuts, Chestnuts, Red Oak, Buckeye, Large Pecans, Shotgun Shells, Golf Balls. For larger items (black walnuts) consider larger style.

Pruning Simplified: A Step-by-Step Guide to 50 Popular Trees and Shrubs

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Pruning Simplified shows you exactly how to do it. This must-have guide offers expert advice on the best tools for the job, specific details on when to prune, and clear instructions on how to prune. Profiles of the 50 most popular trees and shrubs—including azaleas, camellias, clematis, hydrangeas, and more—include illustrated, easy-to-follow instructions that will ensure you make the right cut the first time.

isYoung Birdlook® Smart Bird Feeder with Camera

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Upgraded Dual Granary Bird Feeder. G11 Smart Bird Feeder with Camera – The upgraded dual granary design allows for separate food dispensing, giving birds the freedom to choose while preserving the food’s original taste. With a 2L extra-large capacity, it reduces the need for frequent refills. The drainage design ensures the food stays dry and prevents spoilage from rain. Ideal as a camera bird feeder for birdwatching enthusiasts. 2K HD Camera & Close-Up Bird Watching. Experience clear bird watching with the G11 smart bird feeder. This bird feeder with camera features a 170-degree wide-angle lens and a 1296P HD camera, ensuring vibrant images and videos. With AI-powered recognition, it can identify over 16,000 bird species (subscription required, first month free) and provides extensive birding knowledge. Its unique design helps attract more birds to your backyard. App Alerts & Super Night Vision. The smart bird feeder camera detects motion within 0.5 seconds and sends instant notifications through the “VicoHome” app. With a 2.4G Wi-Fi connection, you can view real-time updates on bird activity right from your app. The video bird feeder also features night vision, ensuring vibrant images and videos even in low light conditions. Ideal for wild bird feeders, this advanced functionality enhances your bird-watching experience day and night.