We’ve had readers vigorously attempt to deny that there is such a thing as overinvestment and too much capacity. Yet we are seeing precisely that pattern play out in China, as its officials increasingly hector companies in a broad swathe of industries to stop cutting prices to preserve domestic market share. The reason for the alarm is that deflation, when it takes hold, is both more destructive and harder to combat than inflation.

China fans are particularly hostile to suggestions that there is anything amiss in the Middle Kingdom. Yet here, the ever-sharper criticism is coming from Xi on down. So a knee-jerk rejection is not a well-informed response.

To remind readers of some of the bad effects of deflation, which is generally the product of the collapse of asset bubbles:

Generally falling prices (obviously the rate of decline will vary by product/service) means companies get lower revenues. They try squeezing suppliers for lower prices, or failing that, cut purchases or may even shut down product lines as their margins become too thin. They also cut prices to try to preserve their competitive position and cover overheads. That can kick off a spiral of what 19th century economists called “ruinous competition,” with railroads a textbook example

Because wages are sticky, workers are more likely to face reduced hours and firings rather than management trying to get them to accept lower pay rates

Falling prices make it rational for consumers to hold off on spending, since purchases are likely to be cheaper in the future

Deteriorating business profits and high unemployment also lead consumers and businesses to retrench, further lowering demand

Price declines and falling wages (or total pay via hours reductions) further impoverish businesses and consumer by increasing the cost of debt (interest and principal payments) in real terms. That has the effect of enriching lenders relative to the rest of the community, since their loans are now worth more in real terms

Deflation also reduces investment. Incurring costs to put new capacity in place when the economy is in a recessionary slide or even falling into a depression is clearly not a good idea. It’s made even worse by the expectation of lower prices when the new capacity comes on line.

As a result, risky assets like stocks and property do badly in deflationary times. Cash and high quality bonds are the best holdings.

Now to some high-level summaries of deflationary conditions from Twitter:

China is dealing with severe deflation:

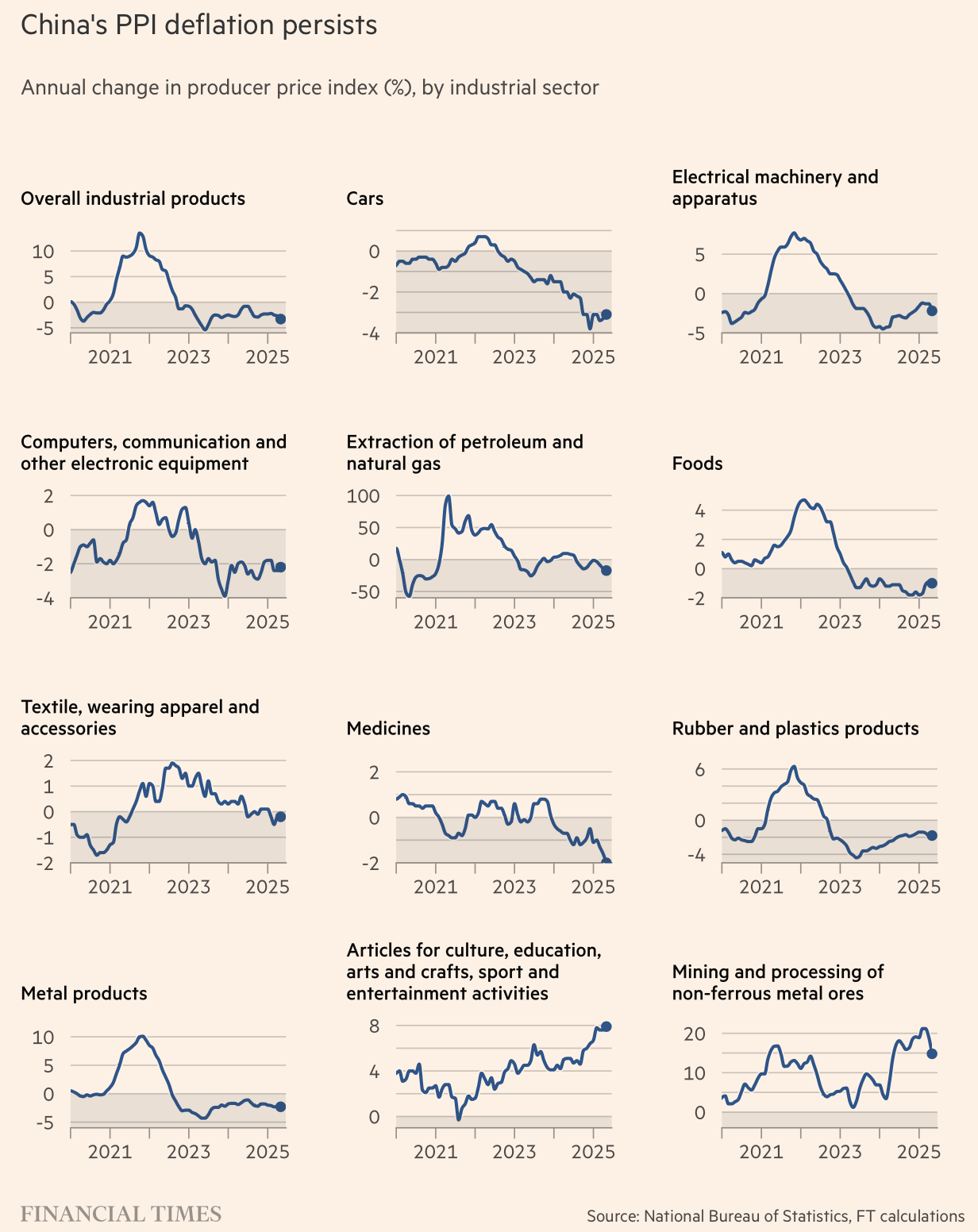

China’s producer prices (PPI) dropped -3.6% YoY in June, the sharpest decline since July 2023.

This also marks the 33rd consecutive month of factory-gate deflation, one of the longest streaks on record.

Meanwhile, the consumer price… pic.twitter.com/rtU8vllhjq

— The Kobeissi Letter (@KobeissiLetter) July 12, 2025

China producer price deflation intensifies. Now -3.6% YoY. No economist forecast that.

The message for the rest of the world is clear. pic.twitter.com/3OUZ0LTNC8— PPG (@PPGMacro) July 9, 2025

China is bumping up against the “impossible trinity.” By choosing not to devalue in response to US tariffs, it also can’t ease monetary policy to counter rising deflationary pressure. China has tied its hands. Not devaluing means it chooses deflation…https://t.co/syJg8vmHpA pic.twitter.com/ukJBWHP4QH

— Robin Brooks (@robin_j_brooks) June 29, 2025

Even before the further decline in producer prices, there have been plenty of signs of too much capacity chasing too little demand in China, with the government lacking good options. Recall that we have repeatedly explained that while interest rates can choke off economic activity, putting money on sale does not induce businesses to go out and expand. The only sectors that might react that way are financial firms and other leveraged speculators.

Consider this sighting of ruinous competition from the Economist in early June, Now China’s ultra-cheap EVs are scaring China:

China’s ability to make electric vehicles (evs) cheaply has caused angst in countries with big carmakers, prompting governments to investigate China’s subsidies for the sector and to erect trade barriers. Now, though, it is China’s own government that is worrying about how cheap its producers’ evs are. The race to the bottom shows no sign of letting up, and the industry has become emblematic of some of the broader problems facing the economy.

On May 23rd China’s biggest ev manufacturer, byd, caused shockwaves when it slashed the cost of 22 electric and hybrid models. Now the starting price of its cheapest model, the Seagull, has fallen to a mere 55,800 yuan ($7,700). The move came just two years after byd had originally unveiled the electric hatchback, at a then astonishingly low cost of 73,800 yuan…..

On May 31st China’s industry ministry told Xinhua, the state-run news agency, that “there are no winners in the price war, let alone a future.” The ministry vowed to curb cut-throat competition, which it said harmed investment in r&d, and could cause safety problems. On June 1st People’s Daily, the Communist Party mouthpiece, argued that low-priced, low-quality products could harm the reputation of “made-in-China” goods.

The backlash comes as leaders crack down on unproductive, self-harming competition between firms and local governments that has created overcapacity and lowered profits….

byd’s shares fell after the price cuts and the official pronouncements, amid concerns that the price war will be unsustainable. But to cling to market share, other carmakers cut their own prices. Wei Jianjun, chairman of Great Wall Motor, one of the largest, called the industry unhealthy and invoked the collapse of the property market as a cautionary tale. “Now, the Evergrande of the automobile industry already exists, but it just hasn’t exploded yet,” he told Sina Finance, a news outlet, referring to the world’s most-indebted developer.

Or from the Financial Times on July 8 in China criticises manufacturers over price war as deflation fears mount, before the producer price figures came in even worse than expected:

China has strongly criticised companies and local governments for fuelling overproduction that it blames for driving down prices..

Chinese producer prices have been mired in deflationary territory since September 2022, posing a challenge for policymakers accustomed to relying on manufacturing and exports to drive economic growth.

In articles across state and party media, Chinese President Xi Jinping and other leading officials have attacked what they call neijuan, or “involution”, meaning excessive price competition….

The statements suggest Beijing is growing increasingly wary that surging industrial output, coupled with weak consumer demand at home, is fuelling a race to the bottom in prices that is entrenching deflation and fuelling tensions with the country’s biggest trading partners..

Overcapacity is a sensitive issue for China, which has sought to dispel complaints that its industrial policy has flooded its partners’ markets with artificially low-cost goods…

The mounting chorus of official concern has stoked speculation that Beijing is preparing to unveil for a bout of “supply side reform”, or government intervention into industries to control prices and reduce capacity…

The Chinese Communist party’s leading policy magazine Qiushi conceded last week that “overcapacity” was an issue…

Chairing a meeting of the party’s Central Commission for Financial and Economic Affairs last week, Xi said: “Efforts must be made to regulate enterprises’ disorderly price competition”.

The Economist, at the end of June, again before China reported its 3.6% year-on-year producer price decline, honed in on Xi’s response in Xi Jinping wages war on price wars:

In May the state reprimanded carmakers not for raising prices, but for cutting them….

Carmaking is not the only part of the economy suffering: factory-gate prices fell year on year in May in 25 out of 30 major industries. In eight, including coal-mining and steelmaking, the drop was even steeper than for cars. Across China’s vast industrial machine, average prices have now fallen for 32 months in a row.

Manufacturing investment, especially in high-tech ventures, has been a bright spot for China’s struggling economy in recent years as it weathers a prolonged property crisis. But the rapid decline of industrial prices and profits has raised doubts about the sustainability of even this capital-expenditure boom. Industries such as electric cars, lithium-ion batteries and solar panels were supposed to be new engines of growth that would fill the yawning gap left by the property sector. Now they have also become engines of deflation…

According to Zhao Wei of Shenwan Hongyuan, a Chinese securities firm, the problem most severely afflicts electrical machinery, steelmaking and products such as cement, ceramics and glass, where prices fell faster than the national average last year. These parts of the economy also suffer from unusual amounts of idle capacity. And, by his reckoning, another 15 industries, from cars to tobacco, show some involutionary tendencies, such as weak profit growth, rapid increases in debt, falling prices or low rates of capacity use….

From 2012 to 2016 China suffered four and a half years of falling factory-gate prices….

China’s planning agency imposed production quotas and capacity cuts on oversupplied industries such as steel. It sought mergers and acquisitions to reduce competition. Coal mines were instructed to operate for only 276 days a year. Officials also strictly enforced standards for energy efficiency and pollution, forcing older, dirtier plants to shut. The policy is considered a success.

[Of the efforts so far this time] These interventions are less bold than those of the 2010s. The campaign may be more tentative because many of its targets are different, says Robin Xing of Morgan Stanley, a bank. In 2015-17 the industries suffering from excess capacity were dominated by large state-owned enterprises. They were easy to boss about…

Many industries now suffering from involution are led by less biddable private firms. Electric cars and solar panels, for example, are dominated by sophisticated commercial enterprises, using cutting-edge technology.

The Economist also notes that weak consumer demand is making this picture worse. The fact that China stopped publishing youth unemployment figures when they were ~20% and are still now guesstimated at 17% or even more says some strong deflationary forces are at work generally in China. As I have said, I’ve seen evidence of China exporting deflation into Southeast Asia via the dearth of much in the way of price increases in the two years I have been here.

Readers can tell themselves that China once pulled itself out of a similar situation. But that was before Trump started his small-bore war on China when he took office, which has now become a much bigger dustup. And as indicated, in the earlier supply-side housecleaning, China could pro-actively engage in creative destruction by accelerating capacity cuts in weak and inefficient enterprises. Now the big sinners in the ruinous competition game are often in China’s most productive sectors, even national champions like EVs. So this issue will continue to bear watching.