In a field where design shapes both public and private spaces, the experiences and worldview of the designer matter greatly. Landscape architecture is not just about aesthetics—it’s also about access. According to the World Health Organization, having access to outdoor spaces for play, gathering, or reflection is linked to lower rates of obesity, of depression, and even of crime. For many, access to green space is a given; backyards, community gardens, and tree-lined sidewalks are part of everyday life. But this is not the reality for everyone. In numerous neighborhoods across the country, greenery is sparse, parks are far away, and outdoor spaces are dominated by industry or infrastructure.

Historically, many communities, especially those of color, were denied access to quality green spaces. Instead of parks and playgrounds, they got highways, overpasses, dumps, and industrial zones. These planning decisions were often shaped by discriminatory policies, whether intentional or systemic. The result is long-standing inequities that continue to disproportionately affect minority populations.

The National Association of Minority Landscape Architects (NAMLA), founded in 2020, was created to increase representation and opportunity for people of color in the profession. Since its founding, NAMLA has become a growing force in mentorship, education, and community engagement, working to address deep-rooted inequities in landscape architecture.

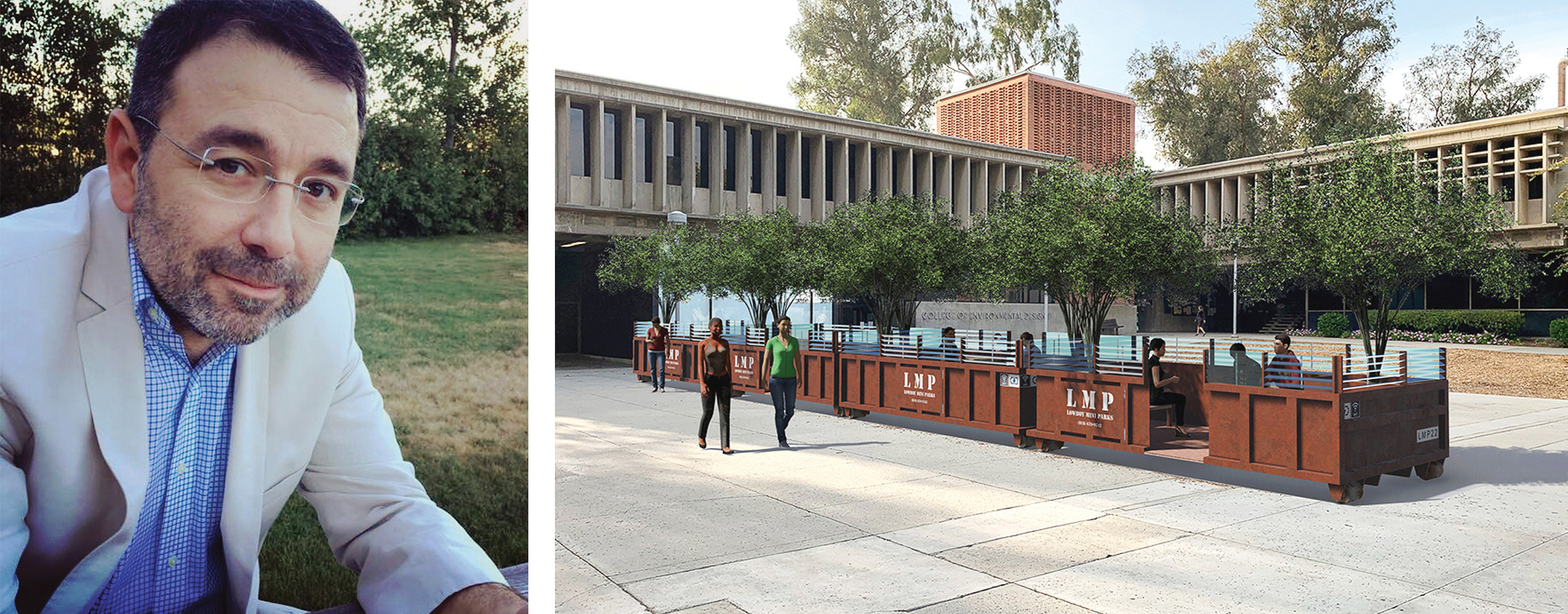

While public awareness of these issues has grown, many of our landscapes, and the profession that designs them, have not kept pace. I spoke with Steven Chavez, one of NAMLA’s founders and its executive director, to learn more about the organization’s mission and the work its members are doing to reshape the field.

CA: Can you tell me a bit about your background and what led you to landscape architecture?

SC: I come from a Chicano Mexican American family, raised in a barrio of LA where there were a lot of custom cars and things like that. It’s part of the culture, lowrider cars. I was the youngest in the family, and I would see my brothers and uncles working on these cars, and I got interested in that. Initially I just loved art and custom painting. Then I got interested in architecture—it’s a little bit of a similar form in some ways, where there’s proportion and materiality—and went to community college to study that field. As one of my general-education requirements, I took an environmental science course, which made me wonder how I could combine that with architecture. Shortly after, I attended a lecture on landscape architecture, and I knew that was it. So I applied and was accepted to the University of Washington Department of Landscape Architecture and got my degree.

|

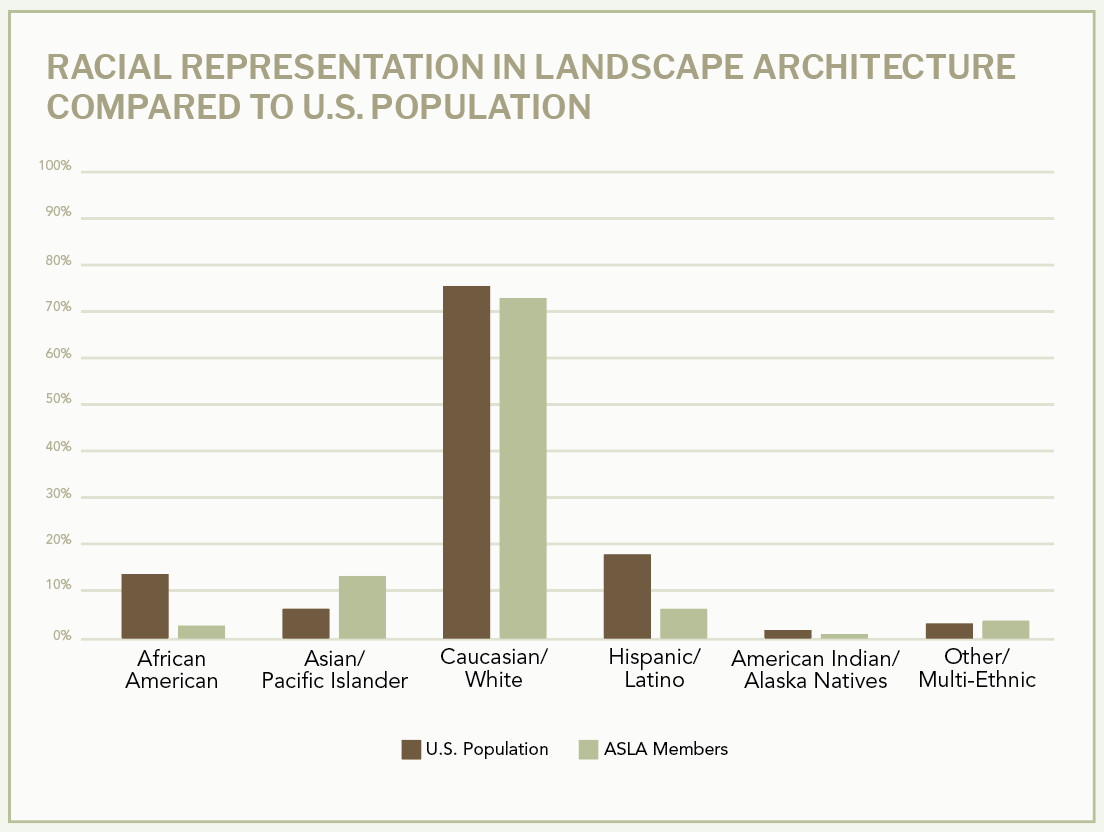

| FACTS AND FIGURES | Diversity remains an elusive goal Despite increasing diversity among students, the landscape architecture profession still skews heavily white and male, especially in leadership. The graph below compares the racial breakdown of ASLA membership with that of the broader U.S. population, revealing significant disparities in representation across ethnic groups. Additional data from the Council of Landscape Architectural Registration Boards (CLARB) also indicates this imbalance: only 7% of licensed landscape architects identify as BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, or People of Color), and just 30% are women, underscoring the profession’s continued lack of diversity.

|

CA: How did growing up in LA shape your design sense?

SC: Los Angeles developed rapidly, especially in the mid-20th century, and so a lot of infrastructure was getting built without much time to really think about how it was going to affect the natural environment.

Then I moved from LA to Seattle, and Seattle was like a city in a giant park. And that influenced me like, “Wow, look how beautiful landscapes can be designed,” and how much it can affect your mood, and how much you feel attached to the landscape and the place. The difference between the two definitely impacted how I felt about what landscape architecture can do. Coming back to Los Angeles, I started thinking about the potential and how landscape architecture could be applied to repair some of these areas.

| GOOD TO KNOW |

What is redlining?

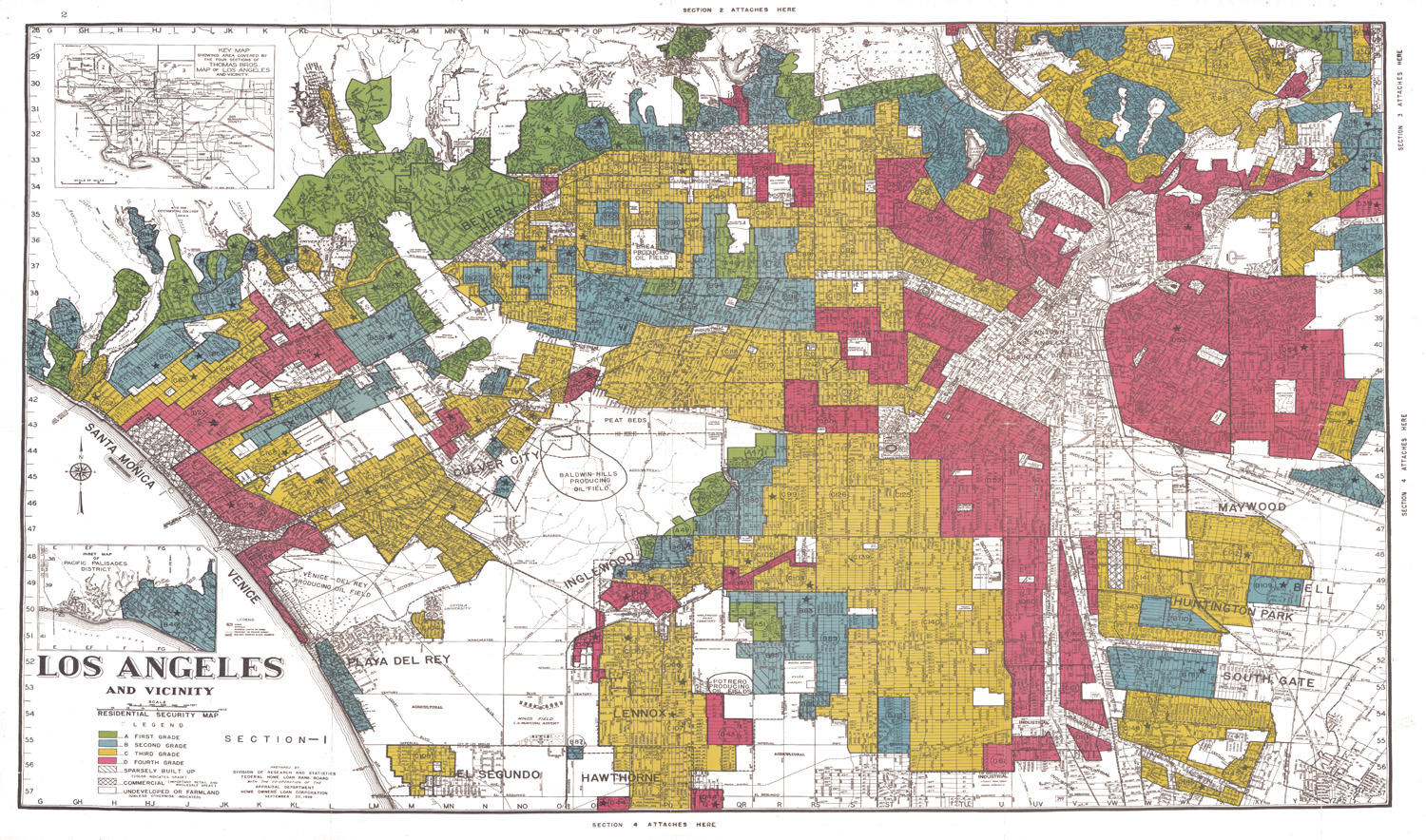

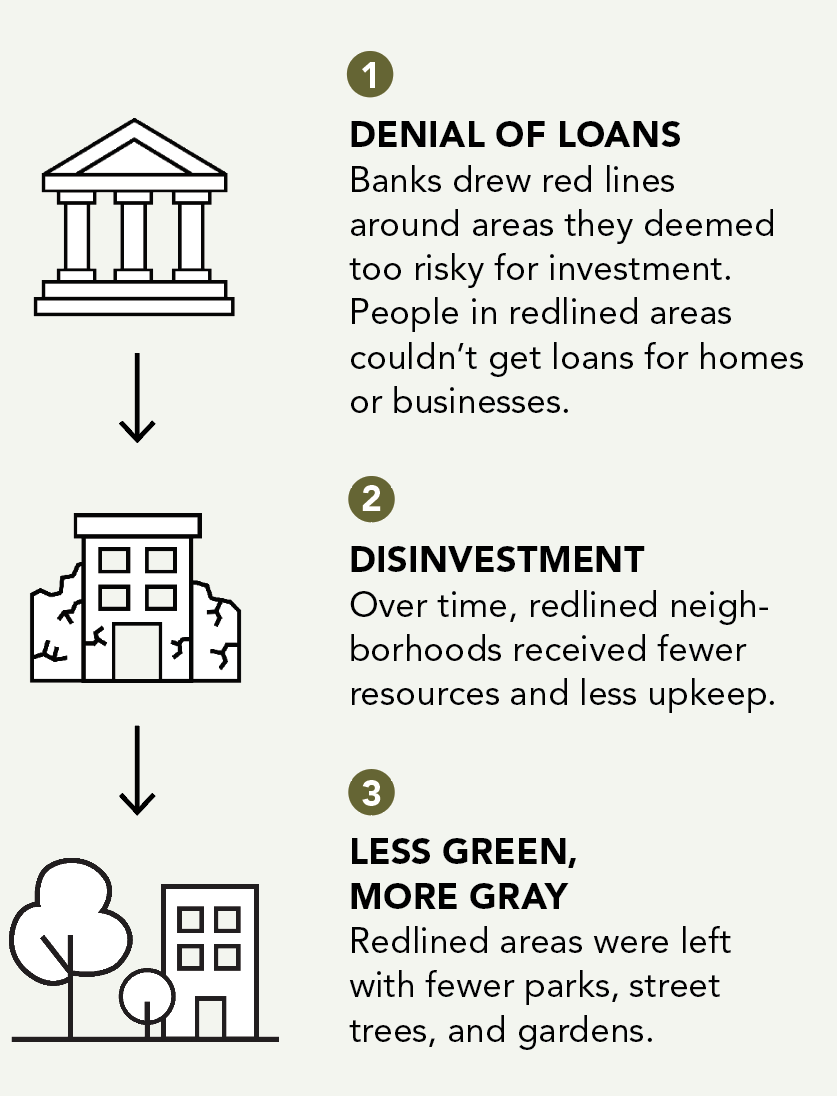

Often called the “invisible blueprint for inequality,” municipal redlining has caused a fracturing of many urban communities across the United States. Here is a quick primer about the policy and its historical legacy on green spaces. Redlining maps were introduced in the 1930s as a federal policy to guide investment in cities. Neighborhoods deemed “high risk”—almost always communities of color—were outlined in red, signaling banks and insurers to avoid them.

Often called the “invisible blueprint for inequality,” municipal redlining has caused a fracturing of many urban communities across the United States. Here is a quick primer about the policy and its historical legacy on green spaces. Redlining maps were introduced in the 1930s as a federal policy to guide investment in cities. Neighborhoods deemed “high risk”—almost always communities of color—were outlined in red, signaling banks and insurers to avoid them.

CA: What kind of repair is needed in LA?

SC: The historical policy of redlining certain neighborhoods left deep marks. Highways were built through communities, creating noise, pollution, and social division. Majority minority populations are still disproportionately found living in unfavorable conditions, whether they are in flood zones, areas of industry, or downwind from air pollution. My students and I did a study in Long Beach, and we saw that the community of color is downwind from all the air pollution from the port of Long Beach. Upwind of the port, there is a higher income bracket. So those decisions and practices still affect minorities quite a bit.

CA: Why did you start NAMLA, and what are its goals?

SC: In school and in the field, I noticed a lack of diversity. Few people of color were designing, writing, or leading. So a few of us—one student, one practitioner, and myself—started NAMLA in 2020. We wanted to see more people of color with leadership roles or tenured positions in academia, and we wanted to see landscape architecture minority business enterprises procuring work and doing public work, especially in communities of color. Even in majority minority communities, most of the design leaders were not people of color. We want to raise visibility, increase leadership roles for minority professionals, and ensure communities of color are being represented by people who understand them.

CA: Does NAMLA also work directly with underserved communities?

SC: Yes. At first, it was about representation within the profession. Then, as we started to grow, we started to think more about public health and cultural heritage landscapes, and seeing what we could do by working directly with communities. We recently got a grant from the Mellon Foundation to award researchers or practitioners in landscape architecture that are advancing and building new cultural heritage landscapes for communities that are underserved.

CA: Why does representation matter in landscape architecture?

SC: Designers from underserved communities bring lived experience. That context shapes better, more-relevant solutions. And that goes really beyond race; it’s also socioeconomic status and cultural status. I think that’s one thing that landscape architecture has been behind on. New types of culture or new paradigms in landscape architecture have not really developed much even in, say, garden making, because what’s published are the things that the people in leadership positions have access to, rather than folks with lower income levels and different types of cultural backgrounds. Say, for example, graffiti. Graffiti has shaped art and has now become part of the fine-art world in a lot of ways, being displayed in galleries. That emergence of influences from those type of urban conditions into landscape architecture hasn’t really happened.

CA: What are some of your proudest NAMLA achievements to date?

SC: Launching student chapters has been huge. After starting on Instagram in 2020, we quickly connected with students at Florida International and UC Davis. Now we have chapters at schools like the University of Maryland and Texas A&M. These groups give students cultural support and professional connections I wish I’d had in school. Having people that you can communicate with and come up with design ideas that reflect a specific culture, it has been good. And I think the students are going to lead on what happens next.

CA: Do you have an example of how inclusive design has made a difference?

SC: When the subject matter or the design implementation relates to the community directly, a strong sense of belonging can happen. There’s a project happening now in South LA related to the 1940s Zoot Suit Riots. The nonprofit East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, in collaboration with Mapache City Projects, is building a memorial at Maywood Riverfront Park, and the community is really excited. And I think it makes people that come from Mexican American culture or the Chicano culture feel a little bit more connected to the park.

Another great example is Chicano Park in San Diego. When a bridge to Coronado Island was built through a Mexican American neighborhood, the community transformed the space beneath it, once seen as a scar on the landscape, into a vibrant park. Today, it’s a hub for art, culture, and community events. It reflects the resilience and creativity often found in communities of color, what’s known in Chicano culture as rasquachismo: turning something often seen as crude into something beautiful.

CA: What challenges do minority landscape architects still face?

SC: In landscape architecture in general, it’s networking. Usually, the people in the positions of hiring and such are not people of color.

Also, another really big challenge for landscape architects of color is that, even if they do get contracted or hired, they’re expected to create a cultural landscape rather than a contemporary landscape, and they are hired more for their background, their upbringing. In some cases that works, especially in communities where there’s a majority population with certain cultural or local lore. But for a lot of the Black and Brown landscape architects, we don’t want to feel like we’re being pigeonholed into creating certain types of landscapes.

CA: What kind of support does NAMLA offer?

SC: We partner with companies to offer microgrants, portfolio competitions, and now a video/animation award. We also reimburse licensure-exam fees through a partnership with the Council of Landscape Architectural Registration Boards. There are four exams now, and they get pretty expensive. So it helps out quite a bit.

This interview was edited for length and clarity. Learn more at www.nationalamla.org or follow @NationalAMLA on Instagram.

Christine Alexander is the executive digital editor.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

ARS Telescoping Long Reach Pruner

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Telescopes from 4 to 7′. Cut and Hold (160) Blades. Drop forged blades for unsurpassed long lasting sharpness. Lightweight, 2.3 lbs., for continued use. Perfectly balanced for easy pruning.

Ho-Mi Digger – Korean Triangle Blade

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Versatile Tool: The Easy Digger Korean Triangle Blade Ho Mi Ho-mi is a versatile gardening tool designed for leveling and digging in home and garden settings. Efficient Design: Its unique triangular blade shape allows for easy soil penetration and efficient leveling of garden beds or landscaping areas. Durable Construction: Crafted with sturdy materials, this tool ensures long-lasting performance and reliability.

Ergonomic Handle: The comfortable handle provides a secure grip, reducing hand fatigue during extended use. Compact Size: Its compact design makes it easy to maneuver in tight spaces and store when not in use.

Corona® Multi-Purpose Metal Mini Garden Shovel

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Longer Service Life: The blade of this round small shovel is made of carbon steel, which can effectively improve the hardness by high temperature quenching, and the surface has anti-rust coating to avoid rusting. In the process of use when encountering hard objects will not bend and deformation.

Sturdy Structure: The small garden shovel with D-handle, ergonomically designed grip can increase the grip of the hand when using, the handle is made of strong fiberglass, will not bend and break under heavy pressure. Quick Digging: Well-made digging shovel has a sharp blade, and the round shovel head is designed to easily penetrate the soil and cut quickly while digging to enhance your work efficiency.