We have entered a parallel universe when Tucker Carlson, amplifying the concerns of right-wing activist Charlie Kirk, is calling for more financial regulation, here of a relatively new form of extraction called buy now, pay later loans.

Due to buy now, pay later loans not being regulated because they do not charge interest (more on that soon) and they are offered either by specialists that are private like Klarna, or as a minor activity of big public companies like Amazon and PayPal, information about the product is spotty. Nevertheless, this is a nasty product that is designed to take advantage of subprime borrower who are already running up against credit limits. To see the likes of The Economist run a story titled Buy now, pay later is taking over the world. Good shortly after the Kirk interview raising alarms about the scale and damage done by buy now pay later loans is….evil. This product is already too reminiscent of the sort of borrower-destructive practices during the foreclosure crisis that were never remedied and barely acknowledged, from banks persuading naive homebuyers to buy more expensive properties than made sense on their incomes (I had many cab driver tell me unsolicited about that) to servicers using late notification plus late charges and junk fees to compound a single late mortgage payment into a foreclosure.1

An overview courtesy the TCN Network newsletter in July:

Remember when you were 21?

You were probably a lot less financially responsible than you are today…

Looking back, you’re likely glad that spending money you didn’t have was not overly easy. The ability to take out loans for things like a pizza pie, a case of beer, or a pair of concert tickets would have seemed too good to pass up. The purported technicalities of interest rates and late-payment fees could have easily zoomed over your head, appearing not worth considering given your chance to buy what you wanted without opening your wallet up front. It’s a good thing that didn’t exist. It could have made you broke.

Today’s young adults face a different situation. They can fall into debt enslavement over things as simple as groceries or video games, and it doesn’t only happen through credit cards. Those are a disaster in their own right, but at least they exist under a regulated system. This is a totally different ballgame.

Remember these four letters: BNPL. They stand for Buy Now, Pay Later.

Surveys show that roughly 60% of Generation Z makes their month-to-month payments using that modern system. That covers Amazon, Instacart, groceries, clothing, and essentially everything in between. You can finance anything.

Want a milkshake but don’t have the cash? No problem. You can split that $6.99 treat into four installments. The same goes for toothpaste, a new winter hat, and practically anything else you can imagine. Monthly payments for a pair of underwear…

We know it’s easy to blame that story’s borrower for behaving recklessly and putting himself in a bad position. He definitely deserves scorn….At the same time, conservatives should realize that he’s not this tale’s only bad guy. The lender is the chief villain. The people loaning the money are taking advantage of the people borrowing it, enriching themselves as young people obliviously slip into levels of economic disrepair they can’t fix. The lender is the only one who really knows what’s happening. He has more power and more wisdom. That means the moral culpability lies squarely on him.

What is the result of this? Generation Z owes more money than any generation in history…Talk about a recipe for chaos….

If America continues down this path and allows the supposedly all-wonderful unregulated market to keep crushing young people with mountains of debt, you’re not going to like the politics that follow. They will make Zohran Mamdani appear moderate. America’s economic system failing everyday people is the primary reason the 33-year-old socialist is on the cusp of New York’s mayor’s office.

Kirk’s discussion of buy now, pay later starts at 28:51:

Charlie Kirk on how continuing to ignore the debt slavery of Gen Z will lead to revolution.

(0:00) How the Russiagate Hoax Paved the Way for America’s War With Russia

(11:42) Donald Trump’s Fight Against the Intel Agencies

(17:11) What Really Is the Deep State?

(18:42) Why Don’t… pic.twitter.com/lCruWuUMve— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) July 21, 2025

Kirk is correct that is it hard to get good information about the buy now pay later product and its market. One decent source was two CFPB studies, using different samples of buy now pay later customers. One study was from 2023, the other in 2025, but both surveyed the 2020-2022 period.2

The CFPB focused on what it described as the most common form of buy now, pay later loan, with a 25% down payment and then three equal payments two weeks apart.They are offered at the point of an electronic sale. The buyer “applies,” the lender runs what is called a soft credit check3 This type of buy now pay later loan does not charge interest but is subject to fees for late or rescheduled payments, usually $2 to $15. Longer term loans may charge interest rates and they can be as high as 36%.

Even though some affluent customers do use buy now pay later loans, the target is subprime borrowers. From the 2023 CFPB report:

Black, Hispanic and female consumers and those with household income between $20,001-50,000 weresignificantly more likely to borrow using BNPL compared to white, non-Hispanic and male consumers, or those with household income below $20,000. In contrast, those with at most a high school degree were less likely than consumers with at least a bachelor’s degree to use BNPL and consumers with a super-prime credit score are less likely than those with a deep subprimescore to borrow using BNPL.

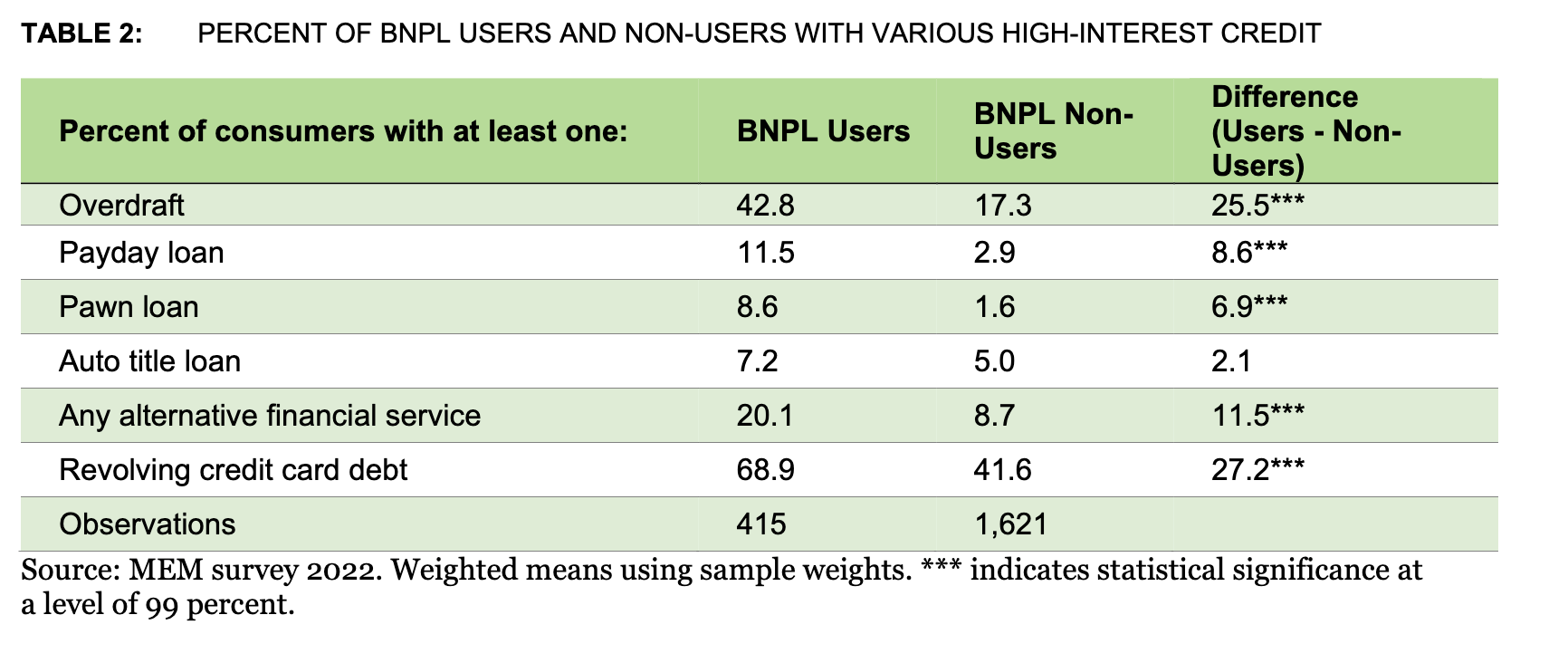

Consistent with the generally low credit scores, buy now pay later users are more likely to be credit stressed. NerdWallet’s overview:

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau released a report in January 2025 that shows the majority of BNPL loans are held by borrowers with subprime or deep subprime credit scores (meaning borrowers with bad credit).

BNPL users also tend to hold larger amounts of other unsecured debts, like credit cards, than non-BNPL users. Though the CFPB doesn’t draw direct conclusions from this report, it suggests that BNPL users may be particularly financially vulnerable and should exercise caution around these apps.

The 2023 CFPB report (recall that both reports were looking at data from mainly the 2020 to 2022 period) found that buy now pay later loans had grown ten-fold between 2019 and 2021. The Economist reported that PayPal, which started buy now pay later lending in 2020, had growth in outstandings of about 20% a year.

Now some of you may be scratching your heads. How can lending to mainly subprime and deeply subprime borrowers make any sense, particularly with such fast credit approval? You might assume that they depend mainly on getting late fees. We’ll turn to that part of the lender’s economics in due course.

But here is the biggie: Buy now pay later lenders get paid first. From the 2025 CFPB report:

…most BNPL firms require customers to set up automatic repayments via their debit card, credit card, or checking account.

So in other words, that buy now pay later loan skims from the borrowr’s available funds or his credit card open balance. That creates the potential for that buy now pay later payment to make the borrower miss other payments. Note they are at high risk of doing so. Again from the CFPB:

BNPL borrowers have lower liquidity and savings on average compared to consumers who did not use BNPL. Approximately 25 percent of BNPL users and non-users alike have zero credit card liquidity, but six percent of BNPL users compared to three percent of non-users with a credit card have negative liquidity, meaning that their debt balances on all credit cards are higher than the sum of their credit card limits, indicating particularly high levels of indebtedness among these consumers.

And they typically rely on high interest credit products:

And of course, a borrower can incur charges on those “source of funds” accounts too. As the CFPB pointed out an earlier report:

Also, be aware that your bank may charge you an overdraft or non-sufficient fund fee if you sign up for automatic repayment through your debit card or bank account and don’t have enough funds to cover the payment

So by dipping their hand in the customer’s funds first, buy now pay later loans ought to have low default rates. Using the afore-mentioned 2020-2022 data, the CFPB found in 2025 that:

BNPL default rates remain lower than credit cards, likely due to automatic repayment requirements. On average, between 2019-2022, BNPL borrowers defaulted on 2 percent of their BNPL loans.

However, this is not as creditor-rosy as it seems. Again using 2020-2022 data, the CFPB found that net chargeoffs were below 4% (and recall this timeframe included the period when citizens were getting considerable Covid assistance, from extended unemployment to rent moratorium) to the degree that poverty fell:

And due to not being able to squeeze water from a stone, the recoveries on buy now pay later loans are lower than on credit cards, so the charge-off rate is worse. From a Reuters story on JP Morgan:

The bank estimated its net charge-off rate, or the percentage of credit card debt that will not be repaid, to be between 3.6% and 3.9% for 2026.

That is higher than the 3.6% net charge-off rate the bank is expecting for 2025.

Moreover, keep in mind that the default rate does not give the full picture of late payments. Buy now pay later customers pay “late” fees not just for missing a payment but also rescheduling one. I have not seen data on reschedulings or a customer missing a payment but then getting current, which would also not amount to a default.

Thus I question the CFPB’s view of the costs of buy now pay later loans. We’ll return to the most common type, per the CFPB, of 25% down, then three more 25% installments spaced out at two week intervals. Per Nerd Wallet, the charge for a late or rescheduled payment ranges from $2 to $15, with higher charges presumably for bigger loan amounts.

We’ll nevertheless assume the lowest charge, of $2, versus the average loan amount of $135 over six weeks. So assume just one missed payment, made up at the next payment time, or two weeks later. $2 for a two week loan of $45. Annoyingly, my corporate finance texts are in storage and multiple web searches are not coming up with the formula for calculating the effective interest rate for a period of less than a year based on the payment, principal, and term. Nevertheless, a $2 fee is 4.4% of $45,4 so this is clearly a super rich interest rate on an annualized basis.

Contrast the forgoing with the Economist’s nauseating promotion of buy now pay later loans, starting with the title: Buy now, pay later is taking over the world. Good.

The last thing the world needs is more private debt, let alone unproductive personal debt that targets the poor and already-overextended. As none other than the IMF determined in 2015, more financial “deepening,” which is economese for more financialization, is bad for growth. And the optimum level is way lower than where the US and Anglosphere are. The IMF put Poland as of then at the sweet spot. It did say more financialization might be possible without a growth cost if there were good regulations. Buy now pay later represents the antithesis of that.

Yet the Economist is all on board with the more efficient creation of debt slaves:

Burritos ordered online, tickets to Coachella and Botox injections. These are not just must-haves for some American consumers—they can now all be bought using buy-now, pay-later financing.

Such purchases are often the subject of derision. Paying for lunch in instalments is, to some, consumerism at its most ludicrous. Others see something darker: lending that skirts the edge of mainstream finance, preying on precarious borrowers.Neither mockery nor anxiety have dented the industry’s growth, however. Worldpay, a payments firm, suggests that BNPL accounted for $342bn in spending around the world last year, up from just over $2bn a decade earlier. Older financial firms, such as JPMorgan Chase and PayPal, have entered the market, just as BNPL companies are taking on tasks that were previously left to banks…

Despite the industry’s recent success, there is reason to think it is still in the foothills. Fewer than 2% of Bank of America customers born before 1965 have an outstanding BNPL payment, compared with 10% of the bank’s Millennial and Generation Z clients. As younger cohorts come to account for more consumer spending, the market should grow. In countries where BNPL has been around longer, it contributes to more sales: over one in five of those made online in Sweden, against less than one in sixteen in America. Local and regional firms are popping up to offer the service: Addi in Colombia, Atome in Singapore, Tamara in Saudi Arabia.

As the industry grows, the borders between BNPL and mainstream finance are blurring. Klarna, an early mover, has been a bank in Europe since 2017. Sebastian Siemiatkowski, the company’s co-founder and boss, says he wants it to become a digital financial assistant enabled by artificial intelligence. Affirm launched a debit card two years ago, and has seen uptake soar of late: the firm now reports almost 2m cardholders. Customers can use the cards in shops, either to pay in full or in instalments, bringing a financing method synonymous with e-commerce into the real world. In the past two years, both the BNPL giants have been integrated into Apple’s and Google’s digital wallets.

Only well into the article does the Economist ‘fess up that most buy now pay later users are already under financial stress. Note it never uses the word “subprime,” let alone “deep subprime”. Instead the positioning is more akin to a new product having growing pains and perhaps at most having a shakeout down the road:

Some difficult questions linger over the industry, which has ballooned over the past decade—a period without a prolonged downturn. Chief among them is whether it is facilitating risky borrowing by consumers living beyond their means.

Customers undoubtedly have lower incomes than those using credit cards. And there have been worrying snippets of news. Klarna’s consumer-credit losses rose by 17% year-on-year in the first quarter of this year. Research by the Federal Reserve suggests that the proportion of BNPL users who have made a late payment has climbed from 15% in 2021 to 24% in 2024.

And in a parallel to the old subprime mortgage market, lenders are being pressed by securitizers and credit funds to gin up more loans. As we explained long form in ECONNED, the “toxic phase” of subprime mortgage origination was the direct result of overheated investor demand. Again from the Economist:

For BNPL providers, expanding their lending operations as fast as possible means keeping a light balance-sheet. The idea of burrito-securitised bonds may be the subject of mockery, but the relatively opaque market for BNPL portfolios is booming. Asset managers and private investment firms that are snapping up the debt believe they have found an appetising asset class in which underlying assets mature quickly. In October, Elliott Advisors, a British affiliate of a mammoth hedge fund, purchased Klarna’s $39bn British loan portfolio. In 2023 KKR, a private-markets giant, agreed to buy as much as $44bn in BNPL debt from PayPal. Affirm has issued around $12bn in asset-backed securities. One BNPL insider calls the market “a feeding frenzy”, where there is not enough debt to satisfy demand.

The Economist tried to legitimate its unseemly enthusisam by arguing that the real opportunity is the small business market. But most small businesses are financially fragile, and small business loans, ex ones against real estate, are guaranteed personally by the owner. So is this just moving up to a bigger ticket weak borrower?

And to return to Tucker, when the right wing thinks the banksters have gone too far, they probably have. As we quoted him earlier:

The lender is the chief villain. The people loaning the money are taking advantage of the people borrowing it, enriching themselves as young people obliviously slip into levels of economic disrepair they can’t fix.

But you won’t learn that from touts like the Economist until the carnage becomes visible, and even then, expect it to be whitewashed.

____

1 This is no exaggeration. For instance, we had a top mortgage securitization executive, also a lawyer, make two months of mortgage payments at once because he was going to be overseas for a bit. His bank credited both payments in one month and still treated him as having missed his payment for the next month. This was in 2003 and with far too much effort, he got it straightened out. But he said, “If this had happened in 2007 or later, the servicer would not have corrected the payment history and I would very likely have been foreclosed upon.”

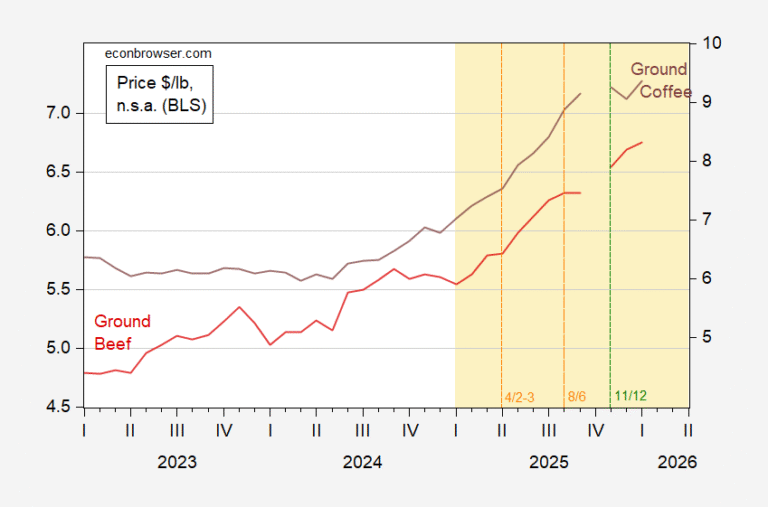

2 Recall that this was a time when Covid subsidies like extended unemployment and rent relief produced a big but short-lived fall in poverty:

3 From what I can tell, the credit bureau delivers the same information as if the buyer was making a credit application, say for a a loan or a new credit card, but puts it in the same category as when credit card companies are screening credit files to make credit offers. By contrast, too many credit applications results in a lowered credit score

4 If you multiply 4.4% by 26, you wold be wrong and would get a failing grade in a finance or investments course.